Which Superalloys Are Most Used for Single-Crystal Turbine Blades and Why?

The Industry Workhorses: Second-Generation Alloys

The most widely used superalloys for single-crystal turbine blades are second-generation alloys, with CMSX-4 and PWA 1484 being prime examples. Their dominance stems from an optimal balance of performance, manufacturability, and cost. These alloys introduced a significant (approx. 3%) rhenium (Re) content, which provides exceptional solid solution strengthening, dramatically improving high-temperature creep resistance and rupture life compared to first-generation alloys. This performance leap enabled substantial increases in engine operating temperatures and efficiency. Crucially, their chemical composition and associated single crystal casting processes are well-understood and reliably controlled in production, making them the benchmark for high-pressure turbine blades in many commercial and military aerospace engines.

Performance Leaders for Extreme Conditions: Third-Generation Alloys

For the most demanding applications, such as the first-stage blades in the hottest sections of advanced engines, third-generation alloys are employed. Key alloys include Rene N5, CMSX-10, and PWA 1497. These materials contain higher levels of Re (often 6% or more) and add ruthenium (Ru) to suppress the formation of deleterious topologically close-packed (TCP) phases that can occur during long-term exposure at peak temperatures. This combination provides the highest usable temperature capability and microstructural stability, directly translating to greater engine thrust and thermal efficiency. Their use is justified in flagship platforms where performance outweighs their significantly higher cost and more challenging casting requirements.

Selection Drivers: Performance vs. Cost vs. Manufacturability

The choice between generations is a classic engineering trade-off. Performance is paramount for front-stage blades, driving the use of 3rd gen alloys. Cost is a major factor; Re and Ru are extremely expensive, strategic elements. For later turbine stages or applications in industrial power generation where thermal cycles are less severe, robust and proven 2nd gen alloys are often the cost-effective choice. Manufacturability is critical; advanced alloys are more prone to casting defects like freckles and require precise heat treatment and HIP to achieve their potential, influencing yield and final part cost.

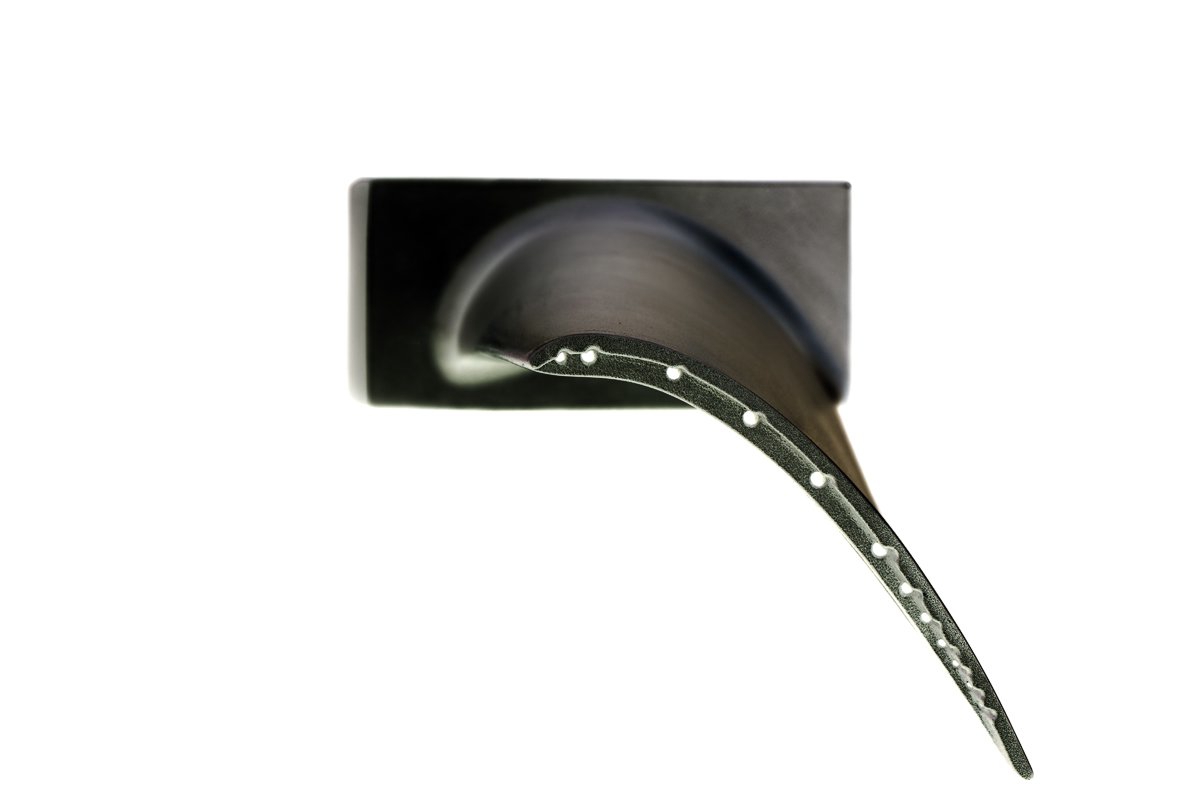

Coating Compatibility and System Integration

A key reason for the selection of these specific alloys is their excellent compatibility with advanced thermal barrier coating (TBC) systems. The alloys form a stable, slow-growing alumina scale at the bond coat interface, which is essential for TBC adhesion and longevity under thermal cycling. The selected alloy must function as a system with the coating, and these generations have been extensively optimized for this synergy. Their microstructural stability under coating deposition temperatures and in-service conditions is a validated characteristic, as seen in partnerships with leaders like GE.

Validated Reliability and Data Maturity

Ultimately, CMSX-4 and Rene N5 derivatives are "most used" because they have decades of validated field performance data. Their long-term behavior under creep, fatigue, and oxidation is exhaustively characterized through engine testing and material analysis. This data maturity allows engineers to design with high confidence in lifespan and safety margins. Newer generations offer better properties but have less extensive in-service history. Therefore, the selection often hinges on a balance between the performance needs of a new engine design and the proven reliability of a mature alloy system.