Why is Directional Solidification Important in Single-Crystal Casting?

Fundamental Principle for Monocrystal Formation

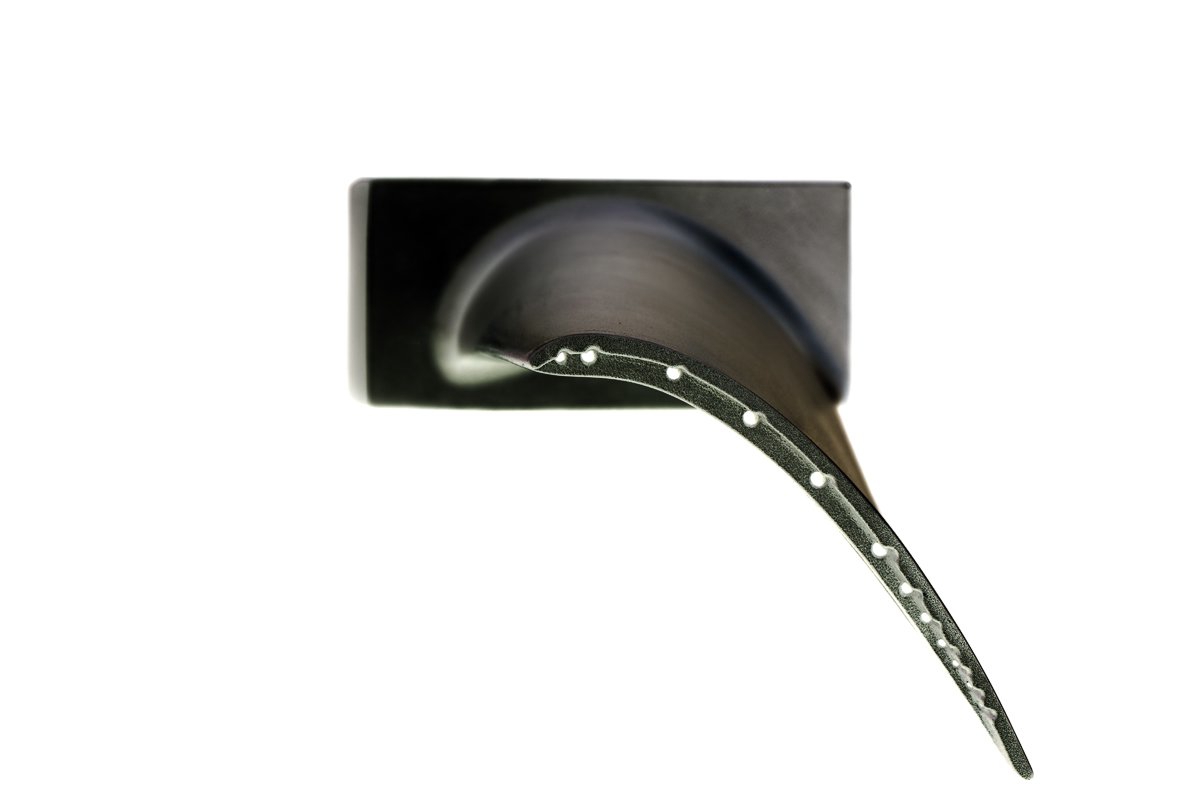

Directional solidification is the essential enabling process for creating single-crystal (SX) castings. It involves meticulously controlling the withdrawal of a molten superalloy from a heated furnace zone into a cooler chamber, enforcing heat extraction along a single, primary axis. This controlled thermal gradient forces the solidification front to advance in one direction, suppressing the random nucleation of multiple grains. A single crystal casting starter seed or a constrictive spiral selector at the mold base allows only one crystal with the preferred crystallographic orientation (typically [001]) to grow upward, forming the entire component as a continuous, boundary-free lattice. Without this directional control, the component would solidify with equiaxed, randomly oriented grains, each with boundaries that are weak points under high-temperature creep and thermal fatigue.

Elimination of Transverse Grain Boundaries

The primary mechanical benefit is the complete elimination of transverse grain boundaries. In conventional polycrystalline materials, grain boundaries are the first sites for void formation, crack initiation, and corrosive attack under the extreme conditions found in aerospace and aviation turbine engines. By using directional solidification to produce a single crystal, these pervasive weak links are removed. This results in a monumental improvement in high-temperature capabilities, allowing components like first-stage turbine blades and vanes to operate at higher temperatures and stresses, thereby increasing engine efficiency and thrust. The process is critical for realizing the full potential of advanced single-crystal alloys.

Optimization of Microstructure and Alloy Performance

Beyond creating a monocrystal, the directional solidification process optimizes the internal microstructure. It promotes the formation of a uniform columnar dendritic structure aligned with the stress axis, which is more resistant to creep deformation. It also allows for the controlled precipitation of the strengthening γ' phase during subsequent heat treatment. The absence of grain boundary strengthening elements (like carbon and boron) in SX alloy design, made possible by this process, enables higher solution heat treatment temperatures. This fully dissolves coarse γ' phases and harmful eutectics, leading to a finer, more uniform, and stable distribution of strengthening precipitates after aging, which is verified through material testing and analysis.

Enabling of Complex Alloy Design and Post-Processing

Directional solidification enables the use of complex, high-performance alloy chemistries that would be unworkable in equiaxed forms. Advanced generations of SX alloys, from first to fifth-generation, rely on this process to achieve their properties. Furthermore, the sound, oriented structure it produces is a prerequisite for effective post-processing. It ensures that subsequent Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) can effectively close micro-porosity without causing recrystallization, and that intricate internal cooling channels, created via deep hole drilling or ceramic core investment casting, are supported by a homogenous material with predictable thermal and mechanical behavior.