What is the difference between single-crystal and polycrystalline casting?

Microstructure Comparison

The most fundamental difference lies in crystal structure. Single-crystal casting produces components with one continuous grain and zero grain boundaries, while polycrystalline casting—such as equiaxed crystal casting—contains many grains separated by boundaries. These boundaries act as pathways for diffusion and crack initiation, limiting high-temperature strength. Eliminating them dramatically enhances thermal stability and mechanical reliability in demanding environments.

Solidification and Processing Differences

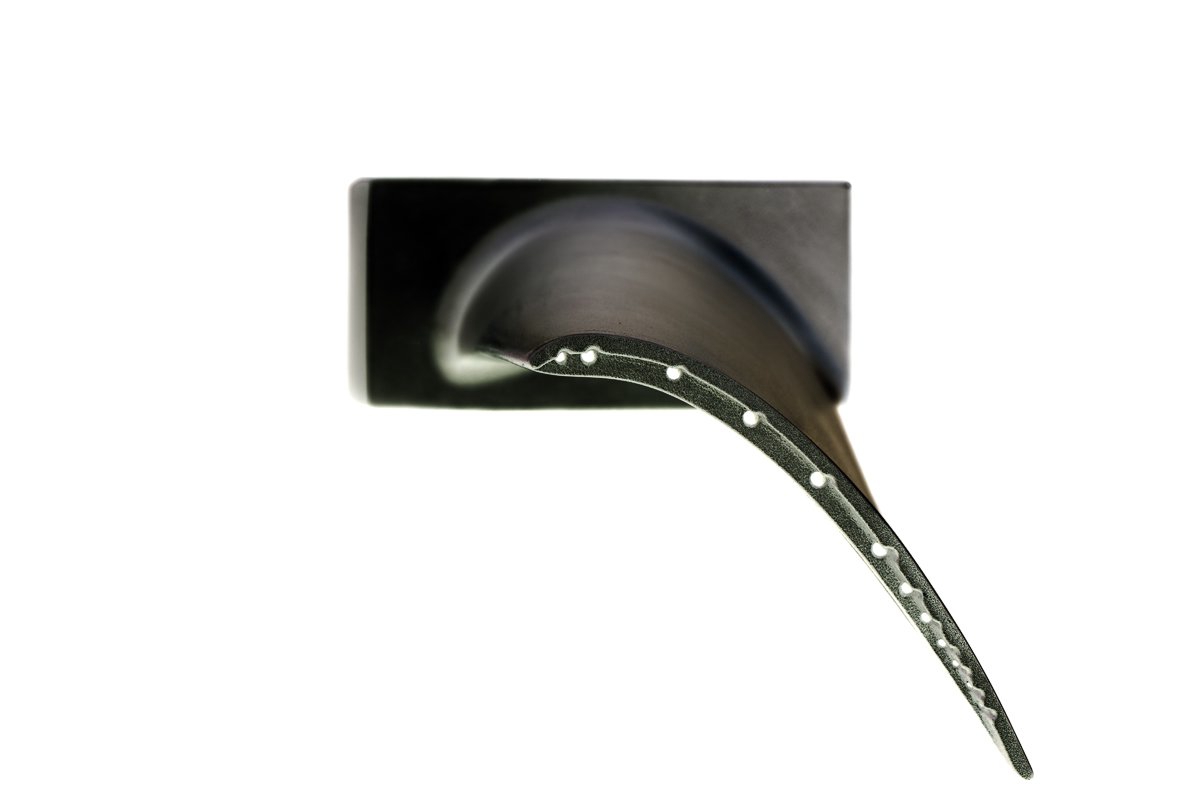

Polycrystalline casting relies on natural nucleation and growth during cooling, resulting in a random grain structure. In contrast, single-crystal casting uses seed crystals and tightly controlled thermal gradients to suppress unwanted nucleation and grow the entire component along a single crystallographic direction. This makes single-crystal processing significantly more complex, slower, and equipment-intensive, but the resulting performance far exceeds that of polycrystalline parts.

Performance and Temperature Capability

Polycrystalline alloys are limited by grain boundary creep, oxidation, and fatigue, especially at elevated temperatures. This restricts their use in the hottest sections of gas turbines. Single-crystal alloys avoid grain boundary sliding and boundary oxidation entirely, allowing them to withstand extreme temperatures often exceeding 1,000°C. These advantages make single-crystal superalloys indispensable for first-stage turbine blades used in aerospace and aviation and power generation gas turbines.

Applications and Material Selection

Polycrystalline castings remain widely used for structural components, housings, casings, and vanes where extreme temperature resistance is not required. However, rotating hot-section components—such as turbine blades, nozzle guide vanes, and combustor hardware—achieve superior creep resistance and fatigue performance only through single-crystal construction. Advanced SX alloys like CMSX, PWA, and Rene families are specifically engineered for this growth method, often combined with post-processes such as heat treatment and HIP to further refine performance.