What causes sliver defects in single crystal castings?

Origin of Sliver Defects

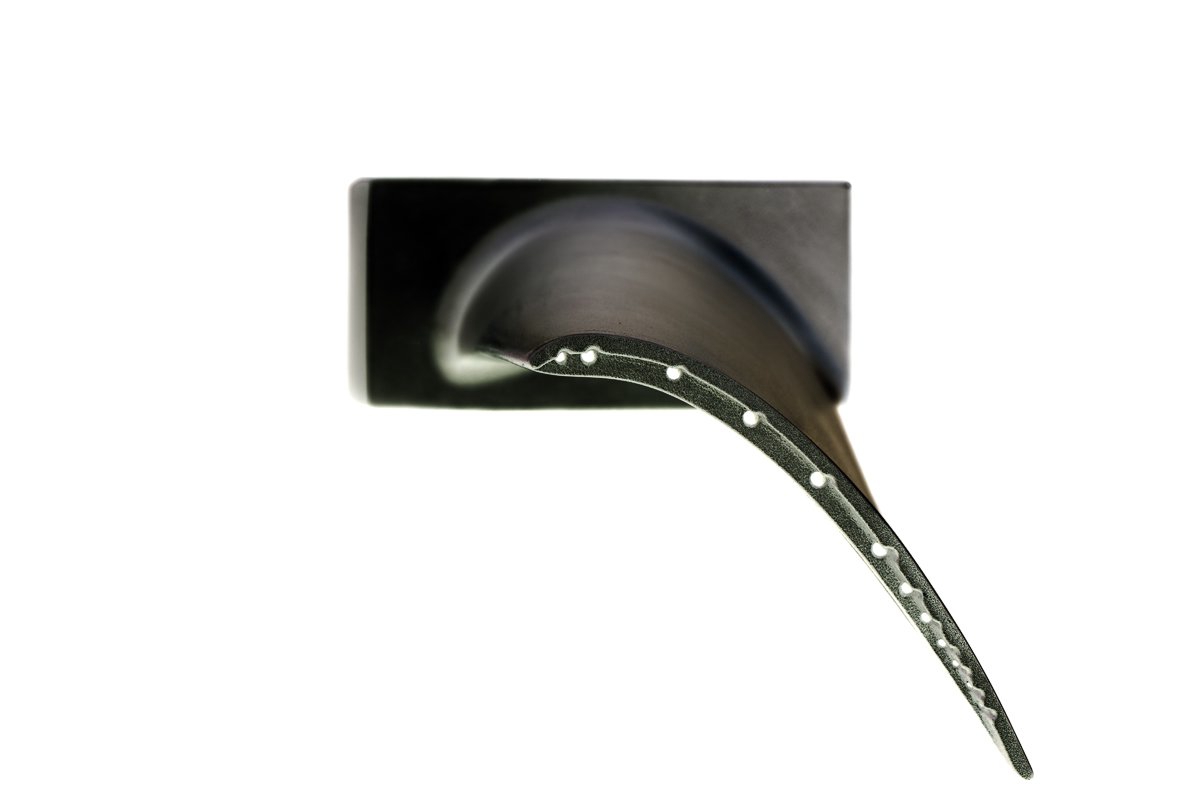

Sliver defects in single-crystal castings originate from the incomplete or unstable growth of dendrites during single crystal casting. They typically form as thin, plate-like regions of misaligned grains near the casting surface. These defects result when the solidification front briefly loses directional stability, allowing short-lived secondary grains to nucleate before being overtaken by the primary solidification interface. Although small, slivers significantly weaken fatigue and creep performance in turbine blades and other high-temperature components.

Thermal Instability and Interface Disturbance

Slivers often develop when the thermal gradient at the casting surface becomes uneven. Local hot spots, inadequate insulation, or sudden cooling changes can cause remelting and re-nucleation at the mold–metal interface. This creates detached or weakly bonded dendrite fragments that grow briefly in misoriented directions. Alloys with high refractory content—such as CMSX-2 or Rene 77—are especially susceptible due to their narrow solidification windows and sensitivity to gradient fluctuations.

Mold Surface Conditions

Poor mold surface conditions are another major cause of sliver defects. Surface roughness, inclusions within the ceramic shell, or irregular mold-wall curvature can create localized undercooling zones. These sites may trigger unwanted heterogeneous nucleation at the interface. Areas with sharp edges, thin walls, or rapid cross-sectional changes heighten the risk by altering heat-flow direction and destabilizing the dendrite front.

Metal Flow and Dendrite Fragmentation

Early-stage metal flow can mechanically disturb the initial dendrite seeds in the starter block or selector, causing fragments to break away and reattach at the mold boundary. These detached dendrite segments may grow temporarily as misoriented grains, forming thin sliver defects before the primary crystal overtakes them. Turbulence during mold filling or incorrect pouring superheat increases the likelihood of such fragmentation.