What causes low-angle boundary defects in single crystal castings?

Origin of Low-Angle Boundaries

Low-angle boundary (LAB) defects in single crystal castings arise when small misorientations develop between adjacent dendrite arms during solidification. Instead of forming a perfectly uniform crystallographic orientation, slight deviations accumulate as arrays of dislocations. When the misorientation remains below ~15°, these dislocation networks form LABs rather than full grain boundaries. Although subtler than stray grains or slivers, LABs still disrupt the ideal single-crystal structure and can negatively impact creep performance.

Thermal Gradient and Solidification Instability

LABs commonly form when thermal gradients fluctuate during directional solidification. Uneven heat extraction—even small variations near mold corners or section transitions—causes dendrite arms to tilt or grow at slightly different angles. These misalignments accumulate and form low-angle dislocation boundaries. Alloys with tight solidification windows—such as CMSX-486 or Rene N5—are especially sensitive to these gradient instabilities.

Mechanical and Shrinkage Stresses

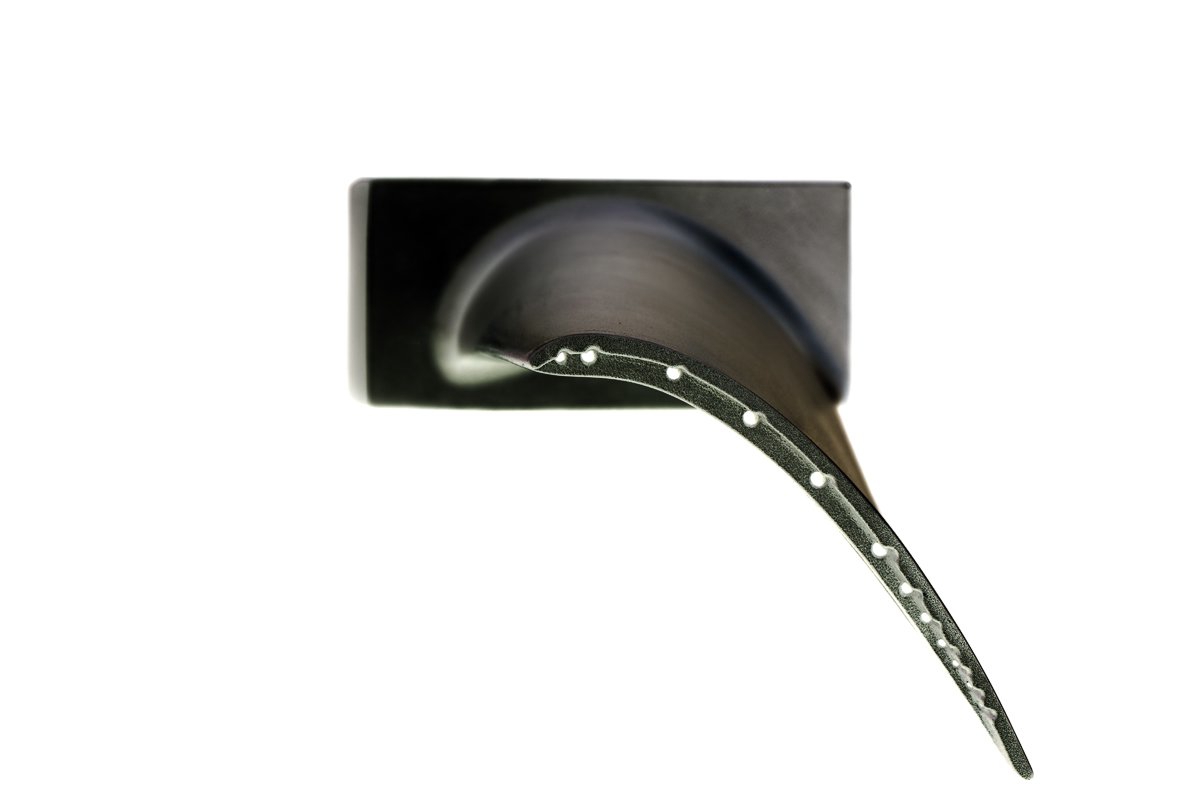

As the casting cools, differential contraction between thick and thin regions can introduce local strain. This plastic deformation increases dislocation density within the crystal. When clusters of dislocations rearrange themselves into ordered arrays, LABs form. Sharp geometric transitions or features such as cooling holes amplify these stresses, making such locations prone to LAB development.

Dendrite Competition and Growth Misalignment

During early solidification, multiple dendrite arms compete for dominance. If misoriented dendrites survive the selector or initial growth region, they may persist long enough to form LABs instead of being fully suppressed. Minor melt flow disturbances, turbulence, or mold-wall interactions can tilt dendrite trunks just enough to produce low-angle misorientation that manifests as LAB defects deeper into the casting.