What are the key differences between single-crystal and polycrystalline turbine blades?

Grain Structure and Microstructural Continuity

The most fundamental difference lies in the grain structure. Single-crystal turbine blades, produced through controlled single crystal casting, have no grain boundaries at all. The entire blade consists of one continuous crystal lattice, typically aligned along the <001> orientation for maximum high-temperature strength. Polycrystalline blades, by contrast, contain numerous grain boundaries that act as weak points under thermal and mechanical loading. These boundaries facilitate grain-boundary sliding, diffusion, and oxidation, reducing performance in extreme turbine environments.

Creep, Fatigue, and Thermal Resistance

Single-crystal blades exhibit dramatically superior creep resistance because they eliminate grain boundaries—the main pathways for creep deformation at high temperature. Alloys such as CMSX-4 and PWA 1480 withstand higher turbine inlet temperatures and maintain dimensional stability for much longer lifetimes. Polycrystalline blades, on the other hand, suffer from intergranular oxidation, fatigue cracking, and creep rupture due to stress concentration at grain boundaries—making them less suitable for first-stage turbine positions.

Alloy Chemistry and Temperature Capability

Single-crystal technology enables the use of advanced superalloy chemistries containing high concentrations of Re, Ta, W, and Ru. These elements strengthen the γ/γ′ microstructure and increase resistance to topologically close-packed (TCP) phase formation. Such complex chemistries would be unstable in polycrystalline form due to grain-boundary segregation. As a result, single-crystal blades operate at temperatures approaching 1,100°C, while polycrystalline alloys are limited to significantly lower thermal regimes.

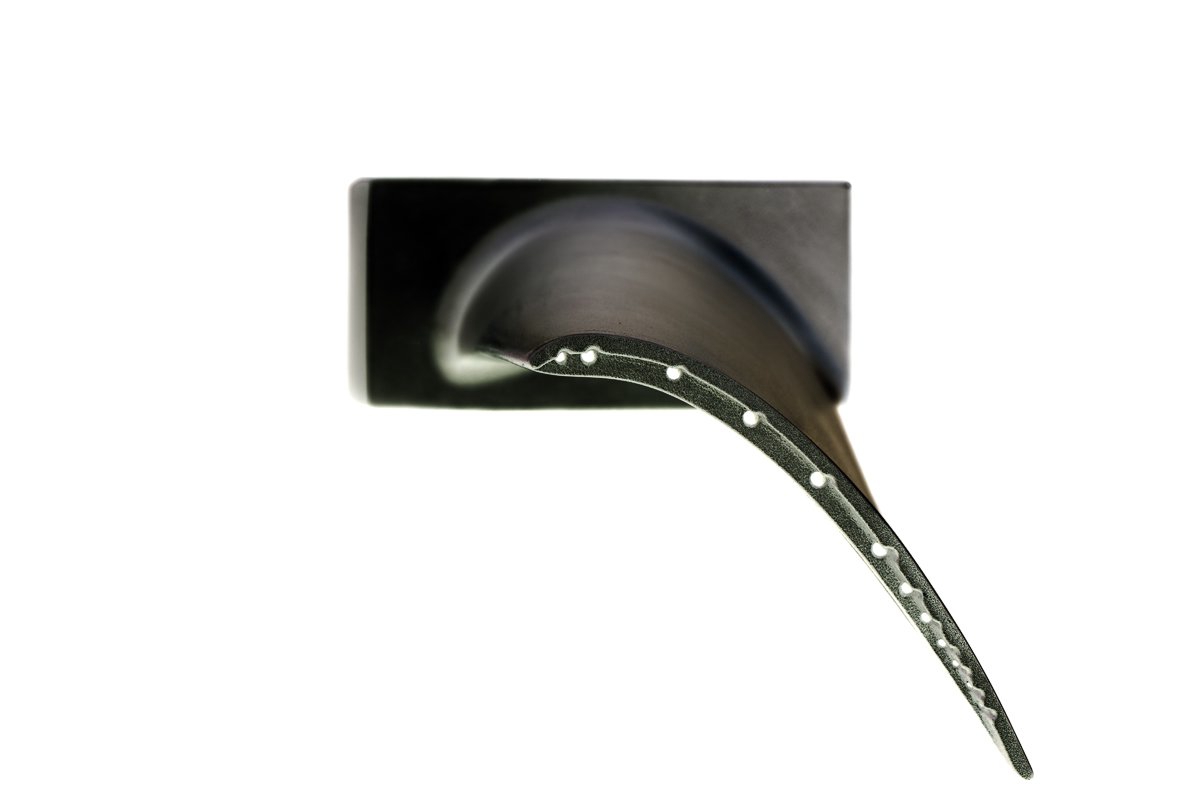

Manufacturing Complexity and Post-Processing

Producing a true single crystal requires precise directional solidification, grain selection, and strict thermal control. Post-processes such as Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) and heat treatment are essential to remove microvoids, optimize γ′ distribution, and maximize performance. Polycrystalline blades require less stringent casting control but cannot achieve the same mechanical or thermal capabilities due to inherent grain boundary limitations.

Application Differences in Turbine Systems

Because of their superior high-temperature strength and oxidation resistance, single-crystal blades are used in the most demanding positions of aerospace and power-generation turbines—especially first-stage high-pressure turbine blades. Polycrystalline blades are typically found in cooler turbine stages or less demanding industrial applications where cost and manufacturability outweigh extreme thermal performance requirements.