How Do Heat Treatment and HIP Improve Anisotropic Properties in Turbine Blade Superalloys?

Foundational Role of Crystallographic Anisotropy

Superalloys for turbine blades, particularly those produced via single-crystal (SX) or directional solidification (DS), possess inherent crystallographic anisotropy. Their properties, such as Young's modulus, creep strength, and thermal expansion, vary significantly with crystal orientation. The engineering goal is not to eliminate this anisotropy but to optimize and exploit it by aligning the strongest crystallographic direction (typically the <001> orientation) with the primary stress axis, while simultaneously mitigating the weaknesses associated with other directions and potential defects. Heat treatment and HIP are complementary processes that achieve this.

Heat Treatment: Optimizing the Anisotropic Microstructure

Heat treatment is the primary tool for microstructural optimization within the anisotropic crystal framework. For SX and DS alloys, the process involves a high-temperature solution heat treatment followed by controlled aging. The solution treatment homogenizes the chemical composition across the dendrites and dissolves irregular secondary phases that may have formed non-uniformly during solidification. This creates a consistent matrix. Subsequent aging precipitates a uniform, fine, and coherent dispersion of the strengthening γ' phase (Ni₃Al). This uniformity is critical: it ensures that the superior creep and yield strength inherent to the <001> orientation are fully realized and maximized. A poorly heat-treated anisotropic alloy can have uneven γ' size or harmful topologically close-packed (TCP) phases, which act as localized weak points and degrade performance off the primary axis.

HIP: Mitigating Anisotropic Weaknesses from Defects

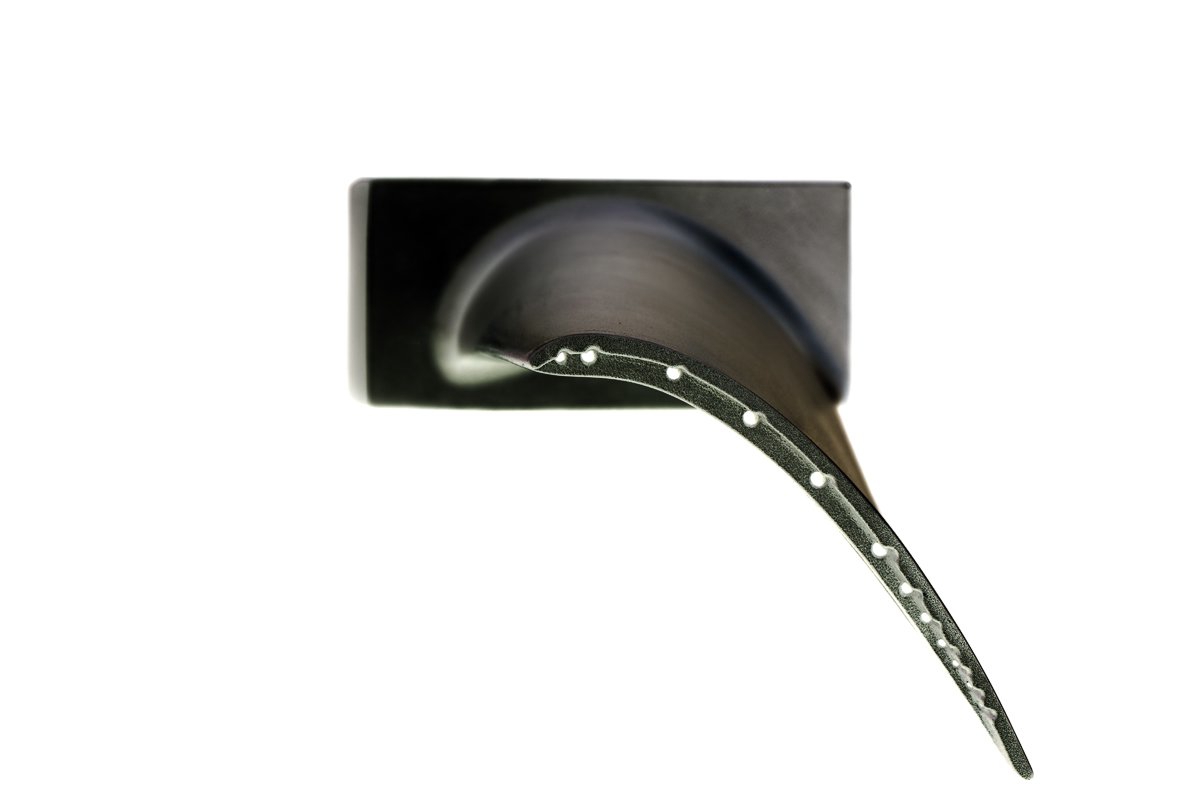

While heat treatment perfects the planned crystalline structure, Hot Isostatic Pressing (HIP) addresses the unplanned physical defects that exacerbate anisotropic weaknesses. Casting defects like microporosity, shrinkage cavities, and freckle chains are rarely perfectly aligned. They act as stress concentration sites, particularly dangerous in directions perpendicular to the strong <001> axis where the material has lower fracture toughness. HIP applies high temperature and isostatic pressure to plastically deform and collapse these internal voids, creating a fully densified material. This homogenizes the material's density, effectively removing random stress risers that could initiate cracks in any direction. For anisotropic blades, this means the designed directional strength is not prematurely compromised by omnidirectional defects, significantly improving low-cycle fatigue (LCF) and thermo-mechanical fatigue (TMF) life across all loading modes.

Synergistic Effect for Multiaxial Stress States

In service, turbine blades experience complex multiaxial stress states despite the primary stress being axial. Cooling holes, platforms, and root fillets create local stress concentrations in multiple directions. The synergy of HIP and heat treatment is essential here. HIP first produces a pore-free substrate with isotropic density. Heat treatment then develops a robust, uniform anisotropic microstructure within that perfect substrate. This combination ensures that the blade's performance is predictable and dominated by its engineered crystal anisotropy, not by random defects. This is validated through advanced material testing and analysis, including creep tests at different angles to the crystal axis and fractography to confirm failure initiates from inherent microstructural features rather than processing defects.

Practical Implementation and Validation

The process sequence is critical. HIP is typically performed on the as-cast condition to heal defects before the high-temperature solution treatment, which could otherwise enlarge pores. The final aged microstructure is thus developed in a fully dense component. For premium aerospace blades in alloys like CMSX-4, this combined post-processing is standard. Validation involves crystallographic orientation checks (Laue diffraction) to confirm proper alignment, followed by mechanical testing. The result is a component whose anisotropic properties are enhanced and made reliably predictable, translating to longer service life in demanding power generation turbines.